Breaking containers and extending our journeys in 2025

Thinking about time as space is one of the most basic and pervasive metaphors out there. As we enter 2025, it is worth thinking about our movements through and in the new year.

Reflections on 2024 describe a year full of extreme weather, shocks and surprises, medical breakthroughs, and, less seriously, meme-ories, and TV characters working out their "daddy issues" the tough way. Anticipating the year ahead, we are told of a storm and dark clouds on the horizon, and another bumpy ride for democracy.

We tend, in these first moments of a new year, to look back and see the year left behind as a coherent whole, a container full of events that can be unpacked and analyzed through retrospection. We then use this careful analysis to infer a map for the year ahead and plan our route through an untravelled landscape whose boundaries we cannot yet see. A container behind, a journey ahead. In this inaugural newsletter, these are the metaphors we’ll consider, thinking about how each may reveal or obscure our understanding of the yearly cycle.

As we move through space, time passes. Without exception, getting from where you are now to wherever it is you want to go will take time. As you move through space, your material conditions also change – you perceive different things, gain and lose access to different objects, and encounter obstacles that require you to move in different ways. Every moment of time can be profiled through spatial affordances – what, in this moment, can you see or touch, what can you reach, how can you move? We learn these correlations between time and space from the moment we gain consciousness in the physical world.1

A moment in time has more than just spatial affordances though. It also has psychological, emotional, and social ones. We feel more comfortable in some spaces than others, more socially connected or isolated. Through abstraction, we learn to associate these non-spatial properties of a moment with space, such that we can be in a bad mood or a relationship, regardless of our physical position. This forms the basis of our Time is Space metaphor – States are understood as locations, and changes in state are understood as movement between locations. For example, you may describe yourself as being in a good place (emotionally) after going through difficult times.

Viewed from a distance, periods of time (such as a year) become bounded regions of space. These bounded regions of space contain locations. For example, you can, literally speaking, say that a town (the bounded region) is full of cute restaurants (locations within the region). The town full of cute restaurants, may also be full of opportunities and activities. These latter concepts don't (directly) take up literal space, but they nonetheless become associated with it. Our Time is Space metaphor then allows us to invert these associations. The span of time itself is what comes to contain all of the events and states we experienced. The year, rather than the town, is full of coffee dates, social activities, and opportunities.

I entered 2024 with Jenny Odell’s Saving Time on my mind, a lovely meditation on how to resist the metaphor Time is Money. And one thing that really stuck with me is the deceptive simplicity of the Time is Space metaphor. Our movement through time, like our movement through space, is uneven.

For me, this unevenness is perhaps most acutely felt while hiking. Even after decades of debunking it first hand, I can’t shake the expectation that a mile is in some way synonymous with a unit of time. It isn’t, of course. A mile with or without a 30 pound backpack, uphill or downhill, over a well-maintained path or one of roots laid bare or sliding scree, all take different amounts of time, literally speaking.

But miles also feel like they take different amounts of time – a mile in the morning is quicker than one in the evening, the mile under soft sun is faster than the mile in rain, and the first mile away from the trailhead somehow takes twice as long as that very same mile returning to your car six hours or three days later – even if, measured in minutes, those miles come out exactly the same.

Odell calls on us to recognize the “flattening” of time that occurs when we structure our lives around hours, weeks, and years. These units of time promise us predictability and consistency – identical bounded regions of space that can be transversed and filled in exactly the same way, again and again. Our calendars and planners are an embodiment of this perceived regularity, with an equal number of lines given to each unit of time.

But we know from experience that this isn't how these hours, weeks, and years feel. As I write this, the day-long week of my holiday vacation is ending, giving way to a month-long week of grading student papers. A year isn't made up of 52 neatly ordered boxes of the same dimensions. Some weeks stretch in our mind. Some collapse inward from the pressures around them. Some contain seven smaller neatly ordered boxes, and some contain an indefinite number of objects melted together from the sun.

We may roll our eyes at the saying Life is a Journey, as it confronts us from the wall of almost every soulless AirBnB and is seemingly one of the only three metaphors your therapist knows. But by embracing our complex subjective experiences of both time and space, we can repurpose even the most clichéd metaphors to reason creatively about the year unfolding in front of us.

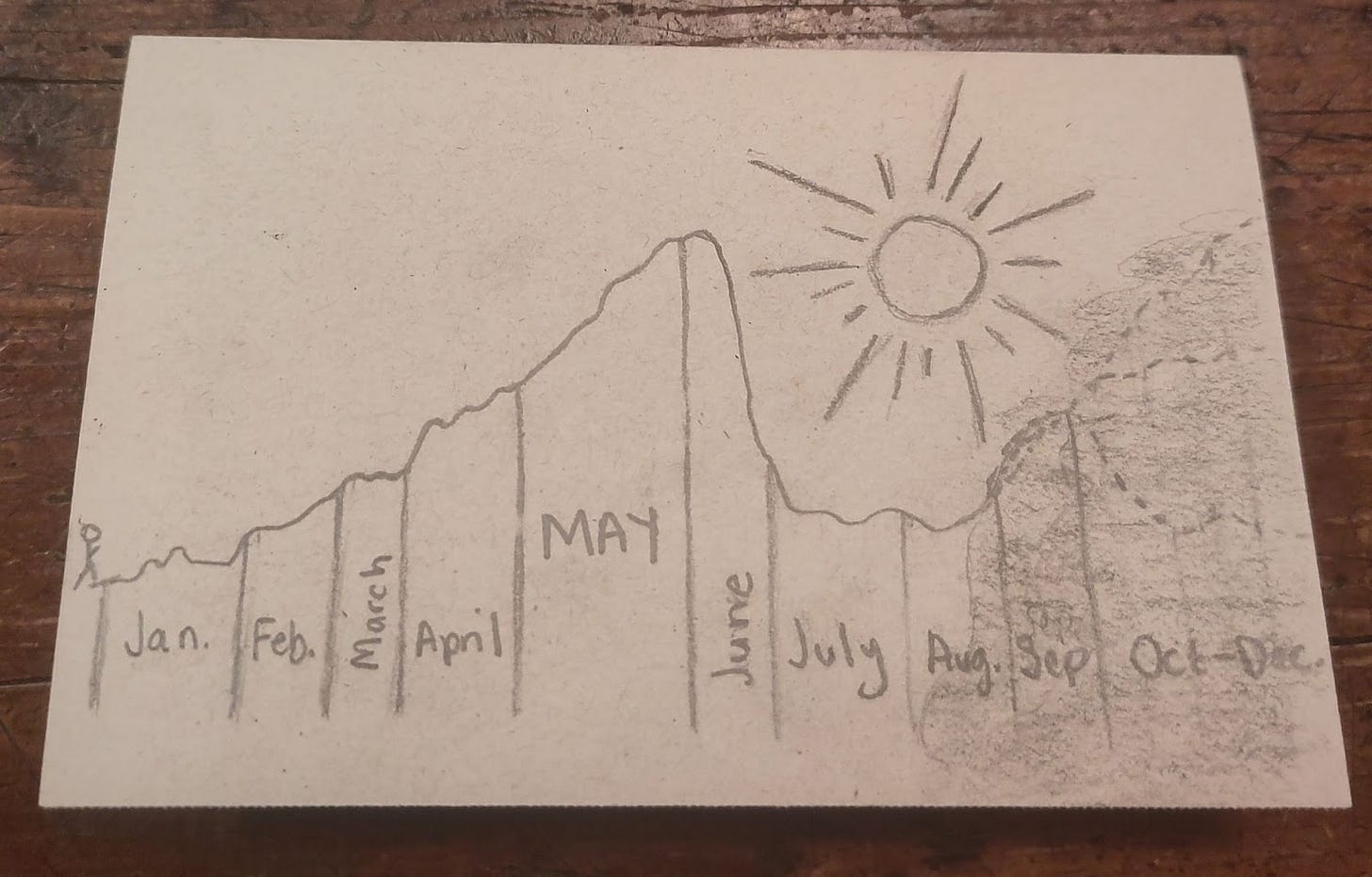

So, here’s my 2025 as a ridgeline. The spring semester is an uphill slog, with intermittent grading scrambles. March, my birthday month, always feels quick and too short. May is going to take forever, with each false summit slowing me down a little more. June, when I finally move back home, is going to be exhilarating, a bit terrifying, and I know the views will be breathtaking. Fall job prospects are an unknown, so there are a few ridgelines of possibility toward the end of the year and still too much fog to plan a sure route.

Resist or Embrace?

Conceptualizing time as space, be it an open landscape or bounded region, is a primary metaphor, ingrained through our lived experiences from an early age. So, well, we’re stuck with it. But we can think about how different creative variants can serve different purposes.

If your 2025 is a container, what do you want to take up the most space? What will fill in the gaps between your larger items, if anything? How carefully will things be organized? Is there anything you’re carrying with you from 2024 that is already taking up space in your 2025? What would happen if you took it out?

If your 2025 is a journey, what kind of journey is it – an adventure, an escape, or a walk in the park? What is your mode of transportation and what would happen if you changed modes? Could you go places you couldn’t before? Do you have enough snacks for the uphill hauls, enough water for the shadeless meadows, and enough good music for the long drive home?

Here in the Metaphor Society…

We’ll frequently wade into contested waters to analyze spicy metaphors in political discourse. But really appreciating the metaphoric foundations of our social systems also requires us to meditate on the more mundane and everyday, to think seriously about the talk that doesn’t seem worth talking about.

The way we think about time shapes how we plan and allocate our material and mental resources across different tasks. Standardized time, metaphorically represented as regulated regions of space, pushes us toward abstracting away from our lived experiences of a messy and complex spatio-temporal world.2 In our meritocracy, we too often tie our self-worth to our productivity, and our “productivity” to normative measurements of how much we can achieve in a set amount of time. Questioning those learned equivalencies is a radical political act.

Move through space differently and feel time expand, then contract. Looking at and feeling the metaphor directly can be liberatory.

Further reading

Interested in nerding out with some scientific literature on the metaphoric relationships between time and space? Here are some suggestions:

Casasanto, D., & Boroditsky, L. (2008). Time in the mind: Using space to think about time. Cognition, 106(2), 579-593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.03.004

Kranjec, A., & Chatterjee, A. (2010). Are temporal concepts embodied? A challenge for cognitive neuroscience. Frontiers in Psychology, 1, 240. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00240

Núñez, R., & Cooperrider, K. (2013). The tangle of space and time in human cognition. Trends in cognitive sciences, 17(5), 220-229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.03.008

This week in metaphor

And to top things off, a wee sprinkle of my favorite metaphor encounters this week.

One. An adorable tea towel by Lewd Linens, given to us by a dear friend. It’s not only a clever and optimistic twist on the resistance is futile saying, but also a pretty gorgeous metaphor. We may typically think of resistance as a kind of negation – not this. The switch from futile to fertile highlights how resistance can also be a positive assertion – not this, and something else instead. Resistance, through negation, makes room for something else positive to emerge and grow.

Two. A reflection on the over-production of information, found in Extended French Theory & The Design Field… on Nature and Ecology: A Reader (pg. 233), a truly fantastic collection of essays.

“We are living amidst a growing mass of ‘semiotic waste’ — in other words, messages, texts and used codes that we cannot get rid of … By their uncontrolled proliferation, the greatest variety of forms, colours and textures can result in the greyest of worlds.”

-Ezio Manzini

‘Semiotic waste’, what a rich concept! Especially when situated within the network of our techno-ecological crises. Can we cut down on semiotic waste like we can food waste or fashion waste? Worth a future newsletter perhaps.

Three. A sneaky journey metaphor, evoked by the reference to “guardrails” for AI and reinforced by the juxtaposition of an unsettlingly cute driving robot.

The guardrails metaphor is a particularly interesting one here – forward motion is maintained, though restricted. This reveals an underlying assumption that progress in AI development will still happen and is, to at least some, desirable.

Four. And… we can’t ignore the immediately memeified cosmic metaphor of the new year: a Tesla Cybertruck explosion in front of Trump Hotel in Las Vegas.

Though I sympathize with the internet’s intuition, I can’t actually pin down exactly what the metaphor is here. And, despite everyone claiming heavy-handedness and a lack of subtlety, I haven’t seen anyone else name the metaphor either. Yes, we have some obvious metonymy (Trump Hotel for Trump, Cybertruck for Musk), and we have at least one primary metaphor (relating the physical proximity of the hotel and car to the social proximity of Trump and Musk). Another, maybe, is a classic metaphor relating power to physical size (that car can’t take on that building). But the whole event, the overarching metaphor? Musk will (metaphorically) explode for trying to cozy up with Trump? That doesn’t seem quite right. Perhaps a step further in abstraction, something to do with the interaction between capitalism and fascism? Maybe. If you have suggestions, let me know.

Coming up next week…

will give a metaphoric breakdown of Justice John Roberts’ End of Year Report. Is judicial independence US Democracy’s “Crown Jewels”? Probably. Chief Justice John Roberts’ defense of these precious jewels? Dubious at best.Then I’ll be back in your inbox the week after with an exploration of how the legal “personhood” of corporations shapes our understanding of violence.

In the meantime, may the metaphors be with you.

The correlation between our experiences of time and space are so ingrained that they frequently become a part of our grammar. For example, in English, we have the “going to” (often pronounced “gonna”) future construction, in which some future event is cast as a physical destination. Pérez, A. (1990). Time in motion: Grammaticalisation of the be going to construction in English. La Trobe University Working Papers in Linguistics 3. 49– 64.

If you find having words for things helpful (as I do), “chrono-diversity” is a good one here. Jenny Odell introduced me to it, but there is a lot of wonderful academic work and reflection on the concept out there waiting patiently for you.

I view the burning cyber truck in front of Trump tower as a metaphor for hope and peace.

Great post, looking forward to reading more! Also, LOVE that tea towel :)