Processes of enclosure and imagining our way out

By limiting the ways we move about our world, we also limit our ability to imagine alternatives. But by remembering how to move differently, we can begin to remember that we can live differently too.

Hello all! It’s been a while. Both Kelly and I are going through a bit of instability right now, so our posts are going to come more irregularly for some time (more on that at the end). For now though, we hope you enjoy this post on enclosure and finding a way out by making art together.

In a recent interview with the Guardian, Charlie Brooker, creator of the dystopian sci-fi show Black Mirror, told us that if we want to see dystopia, all we have to do is look out our window. It’s there 24/7, we’re in it. No subscription service necessary.

Any screen of my too-numerous devices offers an even more reliable stream of “dystopia is here!” content. The news is not good — continuing genocide, my home country sliding into a we’re-not-even-hiding-it-anymore dictatorship, acceptance that 1.5C is gone so we might as well plan for a catastrophic 4C of warming.1 And then there is the constant rage-filled social media commentary, feeling like a collective scream as we all give up.

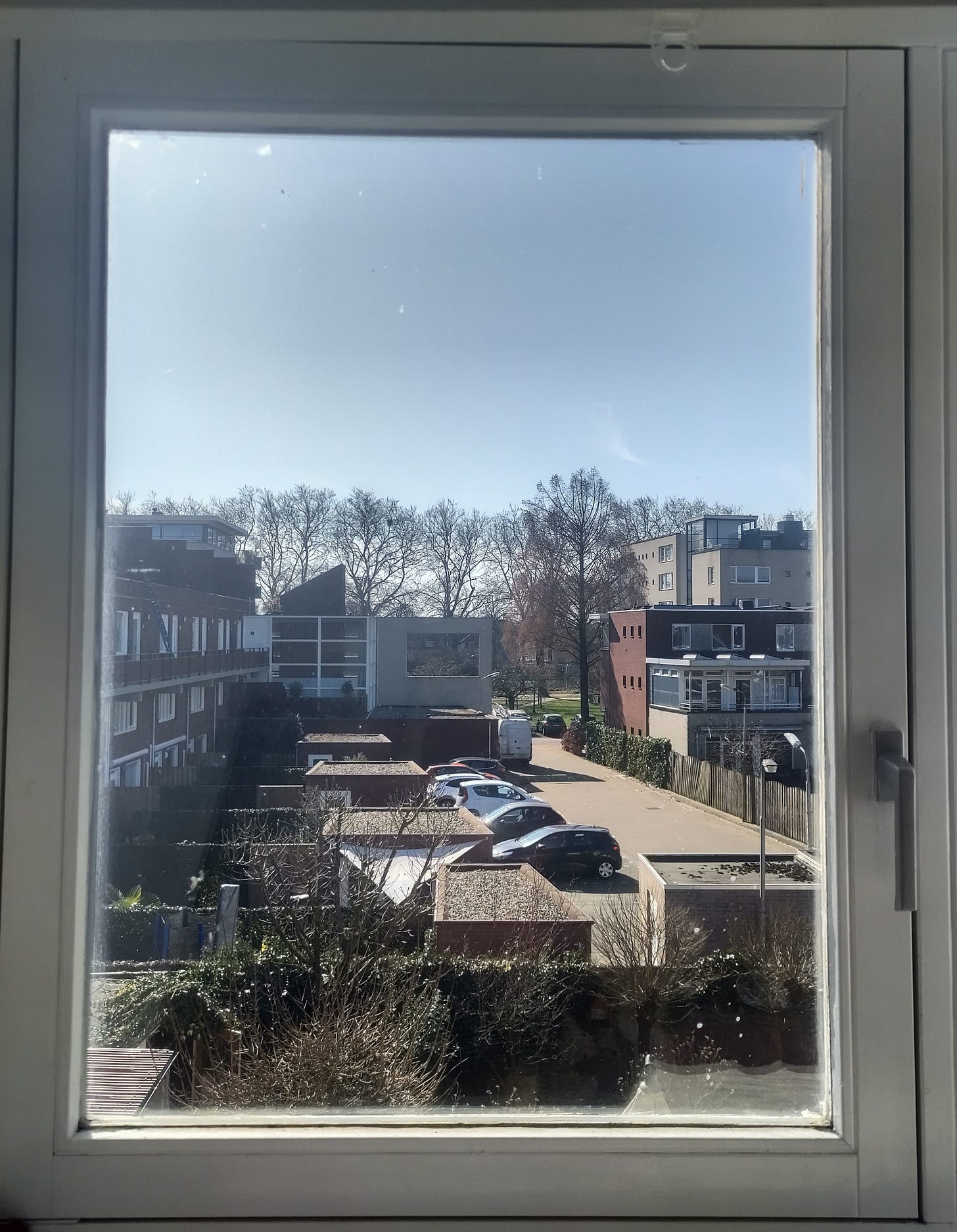

My window seems much more innocent — blue skies this time of year, some trees if you squint, a few mischievous magpies and plump wood pigeons. Or, at least, the dystopia outside my window is a bit more subtle. It’s subtext, not the headline. The skies are bluer than usual because we’re in a climate-crisis-induced drought. The trees are suffering because of it (and, it being a city park in the Netherlands, they don’t offer much in the way of biodiversity support anyhow). The flitting of the magpies and bumbling of the wood pigeons distract from a disturbing lack of other critters (when was the last time I saw a bee or squirrel?).

And then there are all of the things outside my window that I try not to focus on. The cars, indicative of an increasingly car-based infrastructure that makes walking around my pleasant little European city more dangerous, less healthy, and less enjoyable. The sad little walled-in gardens, indicative of the depth of our social atomization. And the one tree in my landlord’s yard, relentlessly pollarded, indicative of an obsession with management and control.2

Dystopia is here now, on our screens and outside our windows. And Brooker’s clever equating of windows and screens exposes something important about how we perceive our relationship to that dystopia — as passive consumers of content, rather than as characters that can fight back with anything more potent than an angry post.

In this piece, I’m going to explore this process of de-agentification, of turning a character into a passive consumer of their own demise, as a form of enclosure. Possibly the ultimate form of enclosure, one that not only restricts our physical access to the world, but also our social, cognitive, and creative access. I’m also going to suggest a way out, a way back into the world, but it will only work if we do it together.

Enclosure: a very brief history

From the late-1500s to the mid-1700s, people of rural England were subject to dramatic changes in how they related to the land. Private property arose as the dominant form of land organization, replacing loose networks of shifting use and responsibility. Bromley3, an actual expert on these matters, sums up “enclosure” in this traditional sense better than I can:

the process of enclosure […] is, the conversion of commonable lands, whether on wastes, commons, or village fields, into exclusively owned parcels, and the concomitant extinction of common rights, of which the most important was that of pasture. (Bromley 2007:2)

So, people went from having negotiable access4 to lands for purposes of grazing, foraging, firewood collection, and leisure, to having either exclusive access (as property owners), highly policed access, or, most often, no access at all. And achieving this transformation toward more exclusionary land use practices required changing not only laws, but also the landscapes themselves and the minds viewing those landscapes.

Traditional enclosure was literally realized in the landscape by growing hedges and building stone walls. It was also represented metonymically, and legally realized, by drawing sharp lines on official maps. But the most important aspect of the enclosure process for our purposes was conceptual — people had to accept that land, as a continuous space in the perceivable and navigable world, could (and should) be discretely and permanently partitioned.

At first, this was met with righteous resistance. Radical groups like the Diggers refused the conceptual shift, and enacted their refusal by levelling hedges5 and continuing to plant crops and graze herds as they saw fit. Now, popular opinion is safely on the side of land as a privatized and commodified entity. Not only do we accept the hedges, we cherish them. Consider, for example, the trope of the white picket fence as a symbol of the American dream.

The unnaturalness of enclosure

When one walks through intact ecosystems, however, one is confronted by the artificiality, the unnaturalness, of discrete static boundaries. The forest encroaches on the meadow as seedlings seek light. The meadows push back with the help of deer who munch on the tender saplings and keep the forest at bay. A constant push and pull. Boundaries unwind to become liminal spaces under constant renegotiation.

The landscape, naturally, is marked by ambiguity and flux. Changing with seasons and life cycles and movements of more-than-human populations that disregard our petty borders. And with each dandelion that pushes through a crack in a sidewalk, we are reminded of this way of the world, of the untenability of our stable lines.

But even with these small nudges, even as we are reminded again and again of the literal untenability of a divided landscape, our conceptualization of a divisible land remains stubbornly intact. We take extreme measures to keep the dandelions out, herbicides, flamethrowers, more and more pavement.

So stubbornly do we cling to this mode of thought that we have extended the process of enclosure to all kinds of metaphoric landscapes, maintaining and policing our metaphoric hedges just as vigilantly as the state does property lines. This comes out in debates about our identities — be it gender, ethnicity, neurodiversity, or disability, we continuously fall into the trap of strictly bounded categories, often in the name of inclusivity and equality, even freedom. We then literalize these boundaries in space, managing our social relations and identities by managing the spaces in which we are permitted to enact those relations and identities. Perhaps more eloquently said:

Social life produces and at the same time employs spatial relations to signify social relations. - The Commoner

It also comes out in how we organize our lives, creating sharp distinctions between work and leisure, chores and play, often in the name of workers’ rights and liberation. It comes out in our problem solving and our envisioning of possible futures beyond the crises we face, isolating the practical and rational from the radical and utopian. We have a phrase, “thinking outside the box”, but its appeal and application is shallow at best.

These discourses on identity and social relations and on how we spend our time are valuable. Necessary. But without addressing forms of enclosure, within and outside of ourselves, these discourses are themselves enclosed. Having accepted, even actively maintained, the hedges for so long, we forget that there is something on the other side. We are unable to see over the hedges to true alternatives. We may not even think to try.

Becoming a (metaphoric) digger

If we’re going to imagine alternatives to the dystopia outside our windows, metaphor can help us in one of two ways. We can try to find new metaphors, or we can make the ones we have more flexible.

In our very first newsletter, I reflected on how entrenched our use of physical space is as a metaphor — time, emotional and psychological states, ideas and project development — all of it is understood, often without us noticing, in the terms of navigating space, traversing a landscape, and being stuck in locations. I argued also that this entrenchment does not have to be limiting, so long as we can learn to occupy and navigate space (literally) in different ways.

I believe that one of the most powerful ways we are prevented from creatively occupying space is our acceptance of enclosure. The literal enclosure of our bodies in privately owned spaces renders the world and our right to changing it inaccessible. Levelling a hedge or removing the fence between neighbors become inconceivable acts. We prevent others from accessing our own spaces with wire, and cameras, and signs loudly declaring “private property” or “no access”. We feel uncomfortable accessing the spaces of others, feeling like perpetual intruders rather than guests. Even our supposedly communal spaces, parks and sidewalks, are meticulously policed — even when we have physical access to such spaces, our forms of access are restricted. No loitering. No foraging. No gathering. Certainly no inhabiting.

Certain counter-culture movements, alive and well, signal a continued sense of unease with this arrangement. Guerrilla gardening, squatting, secret foraging, land back movements, and calls to open one’s unused private property to community use all suggest that contemporary notions of restricted landscapes can still be questioned.6 So far though, they remain stuck in the realm of niche micro-cultures, viewed by those outside of these circles, that is the vast majority of us, with condescension, fear, or disdain. At best, they make for quirky feel-good stories. At worst, they are peddled as criminal signs of the unravelling of our social fabrics.

Fighting enclosure, literal and metaphoric, does not mean a unanimous rejection of private property. It is not, I think, achieving some kind of communist utopia of everything-in-common, for that would be just another form of cognitive enclosure. It means conceptualizing and playing with alternatives. It means unsettling a single dominant framework for interacting with our landscape in order to allow for, even encourage, ambiguity and flux. It is confronting our fear of uncertainty in a world that seeks to carefully define the value of everything, from a parcel of land to a unit of our time. It is Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s assemblage7, Michelle Westerlaken’s many-world world8, Hardt & Negri’s affirmation of singularities9, and Donna Haraway’s process of staying with the trouble10.

As we watch the world go up in flames (literal and metaphoric), we assume the role of observer. This role is facilitated by the omnipresence of our screens — we simply can’t put out the flames that appear in the thumbnail of a Guardian article. This makes us passive consumers of the dystopia we are quite literally and physically living within. And by staying in this consumer role, we are complicit. We are enacting a world in which only the few have the right to determine what our world looks like.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. It wasn’t this way historically. And there are people, right now, enacting alternatives. Levelling the hedges. But those in power will continue to rebuild the hedges, reinforce them, add barbed wire and armed guards, until more of us reclaim our rights to move and occupy our worlds in the ways we want. And, before we can do that, we have to remember that we have the right to imagine, desire, and fight for alternatives.

An invitation

Just as there are many ways to enact, occupy, and transverse our world, there are many ways to go about remembering how to do so. Here, right now, I’m inviting you to try out one way. A small way, simple, low-risk, and fun.

Professionally and personally, I care about embodiment. I care about knowing my body as a physical entity with certain physical affordances that interacts with a physical world. This, I believe, is a precondition for realizing ourselves as agents, as beings that can do things. And so, when I try to imagine better possible worlds, my imaginings are very literal and physical. Everyday. Maybe even a little boring.

I walk down the street and think about how my body would move differently if the space was different. A change in cross-walk design would make my ambulatory commute a little more leisurely, a little less scary. If I were walking through the privately owned forest I pass, rather than along its 10-ft high fence, the air I breathe would be cleaner. If the endless boxwood hedges lining the sidewalk were berry bushes instead, I would be smiling at more birds and could stop every once in a while to savor a berry myself.

I look out my window (I spend so much time looking out of windows) and entertain thoughts of how, if things were just a little different, I might be outside, out there in the world. How instead of clinging desperately to my little inside domain, I could unfold outward and let my body practice other movements, other ways of being.

These imaginings, even if I cannot realize them (yet), give me a sense of agency. By envisioning a different world, even if I can’t literally see it (yet), I maintain hope. And hope, in the face of collapse, is empowering.

The educator in me began thinking of ways to facilitate this same sense of agency and empowerment in others. And this is how the Outside My Window project was conceived. Through a desperation to look out my own window and, if nothing else, see hope in the faces of others.

So, I asked some friends to look out of their windows and send me pictures. I printed their pictures out and invited them over. We co-gathered some snacks and libations. We threw some art supplies on the table. And then we did our best to create images of something else. Something new. Something better.

I came to this event with my own vision, my example of a neatly annotated space, to serve as a kind of prompt. And I was very quickly humbled. My friends’ imaginings were absolutely nothing like what I imagined. They were strange and brilliant. And they were so very different from one another.

Through four hours of laughter, and silliness, and spilling paint, we had created together a many-world world. You can read more about our experiences of that evening here.

More importantly though, you can contribute to our many-world world with your own. The project is ongoing and open. And, I think, the more re-imaginings we gather together, the more we will feel empowered to escape our enclosures, to go out into the world, level some hedges, and dance through re-opened spaces of possibility.

This week (month) in metaphor

The metaphors that caught my eye all had a health theme. Salience of certain countries spiraling healthcare failures, perhaps? Health metaphors are great because they’re both viscerally relatable (we all have bodies, we all like when those bodies work well) and complex (none of us understand exactly how to ensure those bodies work well, but we have a whole lot of ideas). Here’s a handful of my favorites:

This clever skeet from Dave spelling out the parallels (i.e. metaphoric mappings) between Tr*mp and COVID-19. The dissimilarities between the two domains is cued at the beginning by blending “COVID-19” with the year 2025, and then reiterated at the closing, where Dave highlights that the solution to COVID-25 is in fact not the solution to COVID-19.

This excellent public health announcement shared by

. Parasites come in many forms, sucking the lifeforce out of their hosts in many ways. And each one requires a different (but equally urgent) strategy for removal.And finally, keeping with the parasite metaphor, this description of AI as a parasite that may or may not be kept in check.

But A.I. is a parasite. It attaches itself to a robust learning ecosystem and speeds up some parts of the decision process. The parasite and the host can peacefully coexist as long as the parasite does not starve its host. The political problem with A.I.’s hype is that its most compelling use case is starving the host — fewer teachers, fewer degrees, fewer workers, fewer healthy information environments.

An announcement and (another) invitation

Kelly and I (and all of you, for that matter) are going through a lot right now. Kelly is finishing up her PhD (you got this Kelly!!) and trying to figure out next life steps. I’m coming to terms with my imminent exodus from academia and a very uncertain return to the USA. So our goal of a weekly newsletter has been falling a bit short. That means our posts are going to be a bit spontaneous for a while.

With all the additional space, we’d like to invite other writers to join the society with guest posts! So if you have a metaphor you’ve been thinking a lot about and would like to feel out what it’s like to write a blog about it, please let us know!

That’s all for now.

May the metaphors be with you!

-Schuyler

Actually, France, saying “f*ck it, 4C it is, let’s get the bunkers ready” is giving up.

I also think there’s some patriarchy wrapped up in pollarding, especially apparent when it serves no function other than “be the kind of pretty I want you to be”.

Blomley, N. (2007). Making private property: enclosure, common right and the work of hedges. Rural History, 18(1), 1-21.

As Buck (1983) points out, the “commons” of England weren’t a free-for-all. There were rules, both strict and vague. But the shape of land was shifty with lines and rights under constant (re-)negotiation.

Cox, S. J. B. (1985). No tragedy on the commons. Environmental Ethics, 7(1), 49-61.

Somewhat confusingly, “the levellers”, active around the same time, did not participate in these levelling actions, causing some to refer to the Diggers as “‘True Levellers’”.

Gurney, J. (2013). Brave Community: The Digger Movement in the English Revolution. In Brave community. Manchester University Press.

Also the very aptly named Occupy Movement. Though we can argue about how alive and well this particular one is.

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

Westerlaken, M. (2020). Imagining multispecies worlds. Malmö University.

Hardt M. and Negri A. (2009). Commonwealth. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

You know, this really shows how the world feels heavy right now. It’s like everything online is screaming that things are falling apart. But then the view outside seems calm, even though it’s part of the same problem.

I like how the writer notices the little things but still feels the weight of everything going wrong.

I love the general argument and encouragement of the post, to rethink and refigure and challenge the enclosures in our lives, whether they be 'out there,' 'in here,' or both and beyond...and more even than that, the Outside My Window project is fabulous!

To the point at the beginning about Charlie Brooker's playing with the similarities between windows and screens, I think about the wonderful book by Anne Friedberg from 2009, The Virtual Window. Have you seen (through) it? https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262512503/the-virtual-window/